This article explores how data-led analysis can challenge long-held assumptions about where healthcare services are best located. Drawing on geospatial mapping, real-world travel data and live projects, it examines the case for town-centre, hub-and-spoke models of care and the role of underused high-street buildings in improving access, equity and system efficiency. The article argues that placing healthcare where people already are is critical to delivering integrated, community-based services and unlocking wider social and economic benefits.

Imaginative and efficient use of data mapping can challenge ideas about where healthcare is best placed, writes Lead Architect Jaime Bishop.

In 2020, I co-authored an essay that was shortlisted for the 2021 Wolfson Economics Prize. The question I and my collaborators – a fellow architect, a healthcare planner and a social care planner – responded to was: How would you design and plan new hospitals to radically improve patient experiences, clinical outcomes, staff wellbeing and integration with wider health and social care?

Rethinking Where Hospitals Belong

Hospitals built since the inception of the NHS have typically been in suburban or out-of-town locations. Our essay The Well-Placed Hospital maintained that the hospitals of the future must be fully integrated networks of services in a hub-and-spoke mode – the hub being a small but perfectly formed acute general hospital within a town centre. GP practices on high streets were our inspiration, as well as the Darzi-style polyclinics of the early 2000s. We argued that centrally placed services enable equitable access to healthcare weighted towards the most vulnerable users. They take advantage of latent capacity in transport and public amenities and help to regenerate beleaguered town centres. Our assertions were supported by evidence from geospatial mapping of real-world data.

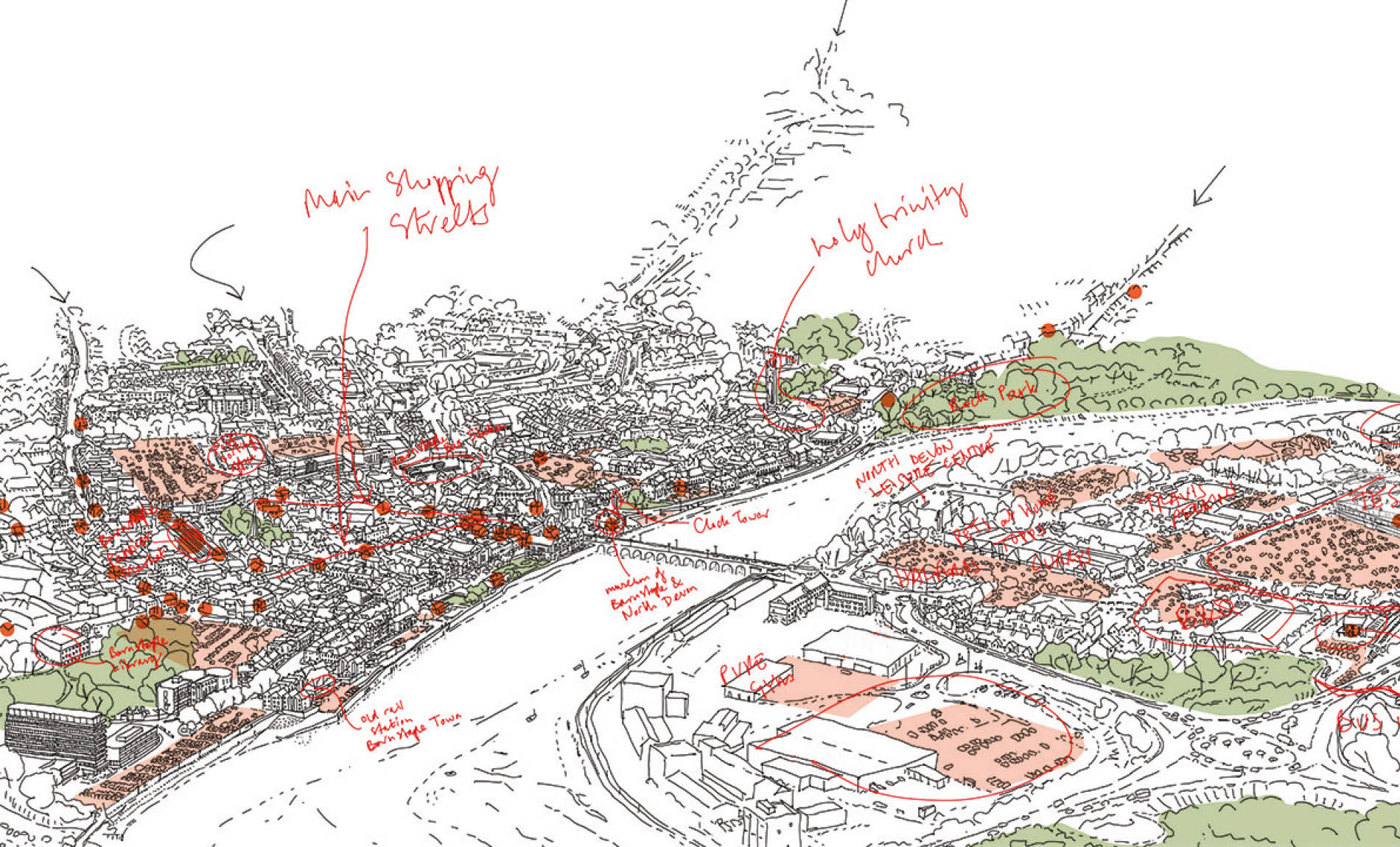

Sketch: by Jaime Bishop

Using Data To Place Care Where People Actually Are

With the help of my practice Fleet’s sister organisation, place + purpose CIC (a community interest company founded by trained architect Tim Kershaw), we conducted a geospatial analysis of every single NHS acute hospital’s main facility. We established the location of its users from publicly available hospital catchment data and measured the travel time for the entire catchment population to the facility. We then located the nearest town centre to each facility and conducted the same analysis. The difference was startling – public transport, car and active travel times to town centres were so much less than to hospitals. When we selected a representative sample of a dozen hospitals across the country, we also found that parking costs were typically lower in town centres. In the essay, we considered vacant building capacity – after all, the greenest building is the one you already have. My team was actively promoting the idea of ‘Health on the High Street’, having worked on the conversion of a disused Matalan into a ‘Civic Supermarket’, housing GP services and aggregated community health services (such as audiology, MSK and dentistry) alongside a children’s library, Citizens Advice and Adult Education Services.

In collaboration with place + purpose and Health Spaces, we now regularly apply data modelling and analysis tools to better understand where particular care services can and should be located. The largest exercise Health Spaces has undertaken so far is the analysis of potential locations for Community Diagnostic Centres (CDCs) in Norfolk and Waveney. We found that access to diagnostics in a sparsely populated rural county was not best serviced by reusing existing non-acute estates (which the NHS is under pressure to do), but by locating high-footfall, short appointment services within the major market towns, which people could access using the reasonable cross-country bus coverage.

Other current projects include two former Debenhams stores ready for repurposing. One will become a four-theatre elective care centre, re-using a colossal structure blessed with a generous concrete frame and offering opportunities to revitalise a town centre with up to 400 full-time equivalent staff; the other will be a compact ‘mini hospital’ – perhaps the closest idea yet to the well-placed hospital we envisaged in the essay – which will bring a range of theatres, recovery, critical care, endoscopy and diagnostic imaging to an underused shopping centre.

Though we are seeing a gathering of momentum, any organisation attempting a Health on the High Street project should not underestimate the hurdles, from managing the change for staff, to the obstacles in the way of Trusts and partners taking on leases. However, the collective rewards are huge, and pathfinder projects such as place + purpose should light the way. So, when you next hear someone – possibly an architect – state that the greenest building is the one you already have, remember it is: but only if it is well placed. Though we are seeing a gathering of momentum, any organisation attempting a Health on the High Street project should not underestimate the hurdles, from managing the change for staff, to the obstacles in the way of Trusts and partners taking on leases. However, the collective rewards are huge…